![]()

![Bishop Raymond J. Boland]()

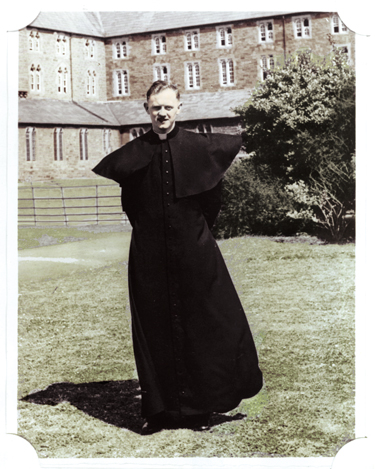

Bishop Raymond J. Boland

Priest and bishop. Son and brother. Irishman and American. Scholar and wordsmith. Genius.

Raymond James Boland was born Feb. 8, 1932, the eldest of what would be the four sons of John and Gertrude O’Brien Boland. He was born with a desire, and a family that nurtured it, to develop fully every gift that God provided him, physically, intellectually and spiritually.

Growing up in Tipperary, County Cork, he was an athlete as well as a scholar. He excelled in the rugged and uniquely Irish sport of hurling — a game similar to the Native American game of lacrosse — as well as rugby, cricket and track.

But pushing himself to find the depth of his God given talents, he excelled also in the classrooms at Christian Brothers College in Cork, and at the National University of Ireland in Dublin.

His first call was to be a teacher, prompted by his early love of great literature. His next was to study architecture.

“God wastes nothing,” he would later joke to the Catholic school fifth-graders at the annual Vocation Days, telling them that as a young priest, he taught literature in schools, and as the Bishop of Kansas City-St. Joseph during a period of remarkable construction, he examined many blueprints.

But Raymond James Boland was to hear another call, not simply to the priesthood, but to the missionary priesthood.

He enrolled in All Hallows Seminary, founded a century earlier to train Irish priests to follow the great Irish migration to the corners of the world.

![Newly ordained Father Raymond J. Boland.]()

Newly ordained Father Raymond J. Boland.

“Early on, I was asked to go to Washington, D.C., which was a new diocese and was short of priests,” he said.

Ordained in 1957, Father Raymond J. Boland served the Archdiocese of Washington, D.C., as associate pastor, youth ministry director, pastor, archdiocesan secretary for education, director of communications, chancellor and vicar general.

“I wasn’t able to keep a job,” he quipped. “I kept moving.”

One job he was given in 1979 was to lead all archdiocesan preparations for a moment in history — the visit of Pope John Paul II to Washington, D.C. It was not only a pastoral visit by the pope. It was also an official state visit from the head of the Vatican to the President of the United States, then Jimmy Carter.

And he had 10 weeks to do it.

Assembling a staff and handing out assignments, he pulled it off — and at a budget of less than $1 million for the two-day papal visit. Later visits by Pope John Paul II would cost some $3 million per day.

It was during that papal visit that Msgr. Raymond J. Boland had a moment he would never forget. Flown in from Ireland as a gift from her sons, 72-year-old Gertrude O’Brien Boland received Holy Communion from Pope John Paul II himself.

Trusting in the Holy Spirit “to do the work,” Msgr. Boland would take on all tasks. But even he became concerned when he saw so many good priests of the Archdiocese of Washington leaving to become bishops.

In 1988, Msgr. Boland had a talk with Cardinal James Hickey.

“You’ve got to stop sending up so many names. We are losing all of our middle managers,” he told his ordinary.

“Two weeks later,” he joked later, “I was appointed Bishop of Birmingham.”

He took as his motto, “Euntes Docete Omnes Gentes” — Go Teach All Nations.

His five years in Birmingham, Ala., would be a foreshadowing of his 12 years as bishop of the Diocese of Kansas City-St. Joseph.

While there, he would oversee the renovation of Birmingham’s cathedral, the construction of new parish churches, and the construction of a new diocesan high school — all done in typical Bishop Boland style.

Bishop Boland’s vicar general in Birmingham, Father Paul Rohling, told of a group of leading Catholics who came to his office to offer their full support in the construction of the new high school.

“He turned that around,” Father Rohling said. “He said, ‘If you build a new high school, I will support you.’”

And support them, he did. Under his servant leadership, the new John Carroll High School opened in September, 1992.

Bishop Boland also took a heart filled with love for the poor to Alabama. Together with Archbishop Oscar Lipscomb of Mobile, he penned the 1990 pastoral letter, “Make Justice Your Aim: A Pastoral Letter on Poverty in Alabama.”

“So many church documents are written for the intelligentsia,” he said. “This one is understandable by the average person in the pew.”

Consulting with all facets of Alabama, from the power brokers and especially to the poor, the two bishops of Alabama examined the economy of their state and nation against Catholic social teaching.

They wrote: “In 1988, Alabama had the highest infant mortality rate in the nation. There are Alabamians who are living in cars, or under bridges, or in shacks with no running water or indoor plumbing. There are Alabamians who go to bed hungry most nights. There are Alabamians condemned to joblessness because of an inadequate education or unavailability of suitable day care opportunities, or simply the lack of a job that would support them. Others work hard at jobs that lack adequate pay . . .

“That so many people are poor in a nation as rich as ours is a social and moral scandal that we can’t ignore.”

In 1993, just as summer was beginning, Bishop Boland received another call. He was to become the fifth bishop of Kansas City-St. Joseph.

In his very first press conference, on the day his appointment was made public, Bishop Boland made clear his vision:

“The parish is where the rubber meets the road. I have had many assignments to parishes and to various apostolates which have enabled me to look at the role of the priest from many vantage points. I have come to the conclusion that the real work of the church is done at the parish level. Everything else that we do should be done to strengthen the parishes and make them vibrant communities of Catholicity.

“The bishop’s agenda is only as successful as the priests make it. I’m very high on evangelization. I have seen some magnificent results in Alabama, where only 2.4 percent of the people are Catholic. . .

“I am also very strongly in favor of Catholic schools and Catholic education of all sorts. I think Catholic schools are still the best way to educate our young people. . .

“Another area where I feel we’re on the cutting edge in the church of the 1990s is in the area of collaborative ministries. By that I mean priests, religious, deacons and laity putting together a parish team in those areas where the work was done mostly by the clergy and religious in the past.”

Before his installation on Sept. 9, 1993, devastating floods along the Missouri River and its tributaries would ravage the diocese from the Iowa-Nebraska border to Carrollton. In his first “official” act as head of the Diocese of Kansas City-St. Joseph, Bishop Raymond J. Boland ordered that no formal reception would follow his installation, held at the downtown Municipal Auditorium to accommodate the crowd, but that the money that would have been spent on such a gala be donated by the diocese to the relief of flood victims.

“This, then, is our pilgrimage — to know God, to know Jesus Christ and to accept him in word and work,” he said in his homily at his installation Mass.

“Prayer, which bridges the gap between human yearning for spiritual completeness and the transcendent reality of a loving God, is the transforming element which nourishes the honest searcher of truth,” he said.

Then Bishop Raymond J. Boland rolled up his sleeves and began his work.

Before 1993 was over, Bishop Boland announced he was strengthening the diocesan policy against the abuse of children by including “zero tolerance” for any church clergy, employee or volunteer.

Nine years later, the U.S. bishops would also adopt the same “zero tolerance” language in the landmark Charter for the Protection of Children and Youth.

As episcopal moderator the National Catholic Risk Retention Group, Bishop Boland with Bishop Gregory Aymond of Austin, Texas, now the Archbishop of New Orleans, developed the “Protecting God’s Children” program adopted by several dioceses, and required of all adult employees and volunteers. The program raises awareness of the plague of child sexual abuse, and trains in the recognition of early warning signs in the behaviors of both predators and victims.

In an address to all Catholic school faculty and administrators during Catholic Education Week in January, Bishop Boland challenged all schools to begin raising endowments as a source of permanent funding. It would replace the priceless gift given by women religious who built the Catholic school system and who, according to the bishop, “worked for a pittance, and when the parish couldn’t afford that, they worked for free.”

Before he retired, several parish schools had built endowments exceeding $1 million.

And the building began.

With the booming economy of the 1990s, parishes began to build new churches, expand existing ones, or renovate their present worship spaces to add beauty. On Bishop Boland’s watch, some 26 parishes built, expanded or renovated their sanctuaries, while 11 built or expanded other buildings including schools and parish halls.

But the best was yet to come.

On July 29, 1999, Bishop Boland announced the first diocesan-wide capital improvements campaign of its kind, the “Gift of Faith” campaign.

With a target of raising $25 million, the campaign had five major goals — renovation of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Kansas City; shoring up education by providing badly needed support for improvements at the four diocesan high schools; fully financing the outstanding liabilities of the Priests’ Retirement Fund; folding in the annual appeal that provided funding for diocesan charitable activities; meeting parish needs by sharing funds with parishes who met or exceeded campaign goals.

On Feb. 22, 2003, Bishop Boland presided as the renovated Cathedral was dedicated.

But as he had done at every parish that had built or renovated magnificent new worship spaces, Bishop Boland reminded that the beauty of the cathedral was not nearly as important as what was to happen inside it for generations to come.

“A church building fails if it does not re-echo the response of Peter when Jesus cleverly inveigled a personal profession of faith from his perplexed apostle,” he said in his homily.

“The very stones around us should proclaim that Jesus is truly the Messiah, the Son of the Living God.”

He continued.

“Here, both today and for years to come, may this holy place be a catalyst of grace, enabling us to understand what is good and what is evil as we ponder our choices between heroism and cowardice, beauty and ugliness, selflessness and selfishness, reverence and abuse.

“May the Lord speak to us as we grapple with the great issues of our time — the morality of war, the dignity of humankind, the ethics of the marketplace and the multiple injustices within our society. And then, conscious that all church doors permit two-way traffic, may we return by the way we have come to share God’s wisdom with the same crowds and those involved in the affairs of men.”

The renovated Cathedral, as well as the beautiful new and renovated churches and schools around the Diocese, is but the physical signature accomplishment of the years of Bishop Boland as leader of the Diocese of Kansas City-St. Joseph.

But of far lasting importance was his spiritual mark.

Facing an increasingly aging population of priests with few younger priests being ordained to replace them, Bishop Boland planned to meet that challenge on two fronts.

He first encouraged deanery planning, particularly in scheduling the number and time of parish Masses, to allow one priest to serve more than one parish, if necessary.

He then expanded the diocesan Vocation Office, which launched programs specifically designed to encourage young people to recognize and hear a call to priesthood and religious life.

Then on Nov. 2, 2002, he called a diocesan Vocations Congress, gathering people from around the diocese, to create a new “climate of vocations.”

He told the hundreds that day that the Catholic Church is a Eucharistic church. Without priests, there would be no Eucharist.

“Suppose you come here on Sunday and there is no priest. You could pray here, but you couldn’t have the Eucharist. If we lose our priesthood, we are no longer the Catholic Church,” he said.

Bishop Boland did not stop there in strengthening the spiritual life of the diocese. He re-instituted the permanent diaconate program, which was wildly successful from its very beginning, ordaining men to serve at the side of the priests in both parishes and in the community.

He also began the Lay Leaders of Prayer program to develop lay people in the skills to restore and conduct devotions, such as the Liturgy of the Hours, which do not require an ordained minister.

“People worry that lay people will preach heresy,” he said. “Well, you can’t preach heresy when you are praying the Hours.”

And, student that he always was, he immersed himself in the history of the diocese, becoming particularly fascinated with another Irishman, Bishop John J. Hogan, the founding bishop of both the Diocese of St. Joseph and the Diocese of Kansas City, which would not be merged until nearly a century later.

In 1999, Bishop Boland made a trip to the parish in Bruff, County Limerick, where Bishop Hogan was born and raised. He unveiled a plaque honoring the original bishop of the two dioceses that the present-day Irishman would serve.

“Although he provided spiritual leadership for emigrants from many nations streaming west in search of cheap land, gold and adventure, he had a special spot in his heart for his beloved Irish,” he told the congregation that packed the small village church.

And so did Bishop Hogan’s Irish-born successor.

Bishop Boland, survivor of one cancer operation and suffering from a blood disorder that would steal his considerable strength and stamina, made another trip to Ireland in the summer of 2001.

Stopping in Tipperary at St. Michael’s Church, where his parents were married and he was baptized, Bishop Boland chose his gravesite, “on the right hand side, immediately inside the railing and immediately behind grave of Father James O’Neill coincidentally also an All Hallows College graduate.”

This son of Ireland was going home.

In a document he entitled “My Personal Funeral Arrangements,” dated Sept. 3, 2001, Bishop Boland has special words for those whom he loved and who loved him.

“It is obvious that God has blessed me in many ways,” he wrote.

“For that reason, I would hope that my passing will not bring sorrow or pain to others because I will be sharing the happiness promised by the Lord of compassion and love,” he wrote.

“It is my prayer and I only ask that, on my behalf, it be yours too, at least for a little while, that the God of mercy will be waiting to welcome me home.”